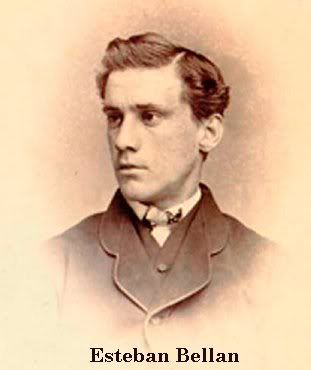

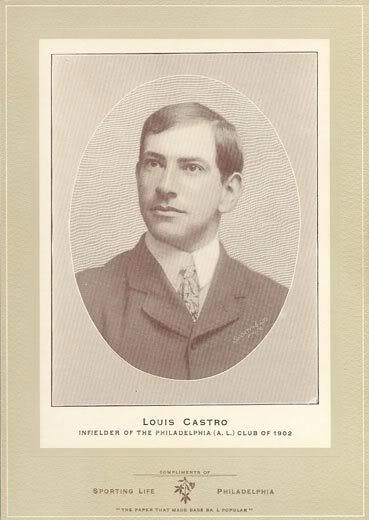

Irregardless of where he was born, it is known that he was born in 1876 (Some dates place it at November 24th). Similar to Esteban Bellan (who was profiled in my last post), Castro played his initial baseball at school while attending Manhattan College in New York City. Some dates place him there starting in 1891 and 1894, but it is known that he played for the Manhattan College team for three years. From there, his baseball experience is within various leagues. In 1898, he played for Utica, 1900 he played for Atlantic City and in 1901, he played in the Connecticut State League. How he came to be discovered by the Philadelphia Athletics for the 1902 season is not known but he did play for the Athletics in the 1902 season.

Irregardless of where he was born, it is known that he was born in 1876 (Some dates place it at November 24th). Similar to Esteban Bellan (who was profiled in my last post), Castro played his initial baseball at school while attending Manhattan College in New York City. Some dates place him there starting in 1891 and 1894, but it is known that he played for the Manhattan College team for three years. From there, his baseball experience is within various leagues. In 1898, he played for Utica, 1900 he played for Atlantic City and in 1901, he played in the Connecticut State League. How he came to be discovered by the Philadelphia Athletics for the 1902 season is not known but he did play for the Athletics in the 1902 season.Due to a contract dispute between The Athletics and their second basemen Nap LaJoie, the second basemen position became available. The manager of the Athletics, Connie Mack, chose Luis Castro to be his second basemen. Here are his statistics for 1902:

Year | G | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | BB | SO | AVG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1902 | 42 | 143 | 18 | 35 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 15 | 2 | 4 | 0 | .245 |

Castro was let go after the 1902 season and played Minor League baseball among various leagues for about 17 years. What he did after baseball is not known but it is known that he lived with his wife in Flushing, NY and died in New York City on September 24, 1941. Pretty straightforward or so it seems.

The debate starts at this point. As per the 1910 census, Luis Castro is listed as being born in Colombia but this changes with the 1930 census where his birthplace is listed as New York City. Why the change? Speculation lies in that he was afraid of being deported. Also, since it is believed that he was in financial straits in his later years, in order to get benefits he may have needed to be a citizen of the United States. Who truly knows. The following piece of information may shed some new light where he was truly born. Based on the research of Nick Martinez, a ship's log of the SS Colon which left Colombia in 1885, a man named Nestor Castro and his eight year old child Luis (who was born in Colombia) were on the ship coming to New York City for business. Instead they stayed in the United States to make a new life for themselves.

So was he the 1st Latino Major Leaguer? If he was born in Colombia, then absolutely. If he was born in NYC, then I guess not if you subscribe to the idea that a person born in a non Latino country to a Latino parent(s)is not Latino. Though my position lies somewhere between both points of view. I believe that at least for the 1st Latino Major Leaguer he should have been at least born in Latin America. For later players, I think that if at least one of your parents were Latino, then you are Latino. Some authors have different views which can be seen in the following links:

Ian Herbert Smithsonian Magazine 9/1/2007

Peter Bjarkman's blog post 9/25/2007

Louis Castro website by Nick Martinez

Jesse Sanchez article on MLB.com 4/23/2007

So let me be devil's advocate for a second. If Castro wasn't the 1st, then who was. I personally think that Esteban Bellan should be listed as the 1st since he played in the Major League of his time (National Association) and whether the MLB, Elias Sports Bureau or any other agency doesn't recognizes it shouldn't change the fact that Bellan played Professional baseball before any other Latin ballplayer. But if we do go with the theory that the National Association wasn't a major league then who should it be. I just found about a baseball player called Charles "Chick" Pedroes who in 1902 played 2 games for the Chicago Orphans who was born in Havana but came to Chicago at the age of 2 years old. So where does he stand. I believe that this issue will only be further developed though research and I hope to be able to bring you some of that research in the near future.

Thanks,

FHJ