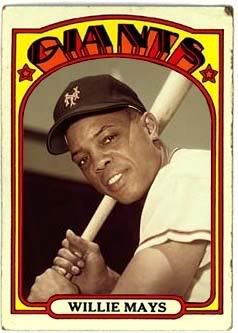

The year is 1954 and the location is Puerto Rico. Playing in the Puerto Rican Winter league on the team known as the Santurce Cangrejeros. Now the 1954 season in the United States was punctuated by the arrival on the national scene of a young 23-year-old named Willie Mays. This was seen specifically with arguably with the over the head catch by Mays off of a blast of the Cleveland Indians’ hitter Vic Wertz during Game 1 of The World Series. In contrast, Roberto Clemente had come off of a frustrating rookie season with the Montreal Royals, which was an affiliate of the Brooklyn Dodgers. It was frustrating in that The Dodgers were trying to hide him from all of the other scouts and wanted him to get proper seasoning by playing a number of years in the minors. So his playing time was limited. In the end, their hesitance to play him worked against him as the Pittsburgh Pirates took Clemente with the 1st pick of the Rule V draft in the Winter of 1955. But let’s get back to Puerto Rico in late 1954.

The year is 1954 and the location is Puerto Rico. Playing in the Puerto Rican Winter league on the team known as the Santurce Cangrejeros. Now the 1954 season in the United States was punctuated by the arrival on the national scene of a young 23-year-old named Willie Mays. This was seen specifically with arguably with the over the head catch by Mays off of a blast of the Cleveland Indians’ hitter Vic Wertz during Game 1 of The World Series. In contrast, Roberto Clemente had come off of a frustrating rookie season with the Montreal Royals, which was an affiliate of the Brooklyn Dodgers. It was frustrating in that The Dodgers were trying to hide him from all of the other scouts and wanted him to get proper seasoning by playing a number of years in the minors. So his playing time was limited. In the end, their hesitance to play him worked against him as the Pittsburgh Pirates took Clemente with the 1st pick of the Rule V draft in the Winter of 1955. But let’s get back to Puerto Rico in late 1954.  So again, you’re sitting in this stadium watching two of the most exciting ballplayers to ever grace the diamond in any stadium and they are playing on not only the same field but on the same team! Now you may ask, how does this happen. The economic reality of the game in those years was much different than today. Where today’s player makes at least six figures at a minimum, players in the 1950’s didn’t make much money. So when the opportunity to play baseball year round in an ideal setting like the Caribbean came along the ballplayers took it. In addition to making more money, players who were either Black or Latino found that the exclusionary racial environment they faced on a daily basis in the United States was virtually non existent in the Caribbean. They were able to dine and go where they wanted and were treated with respect.

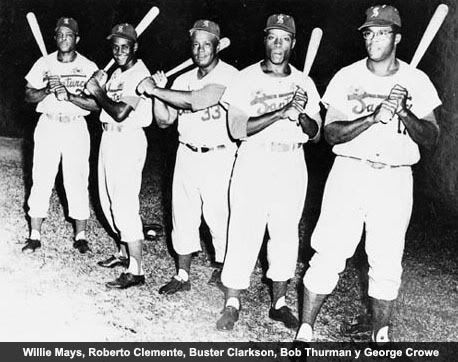

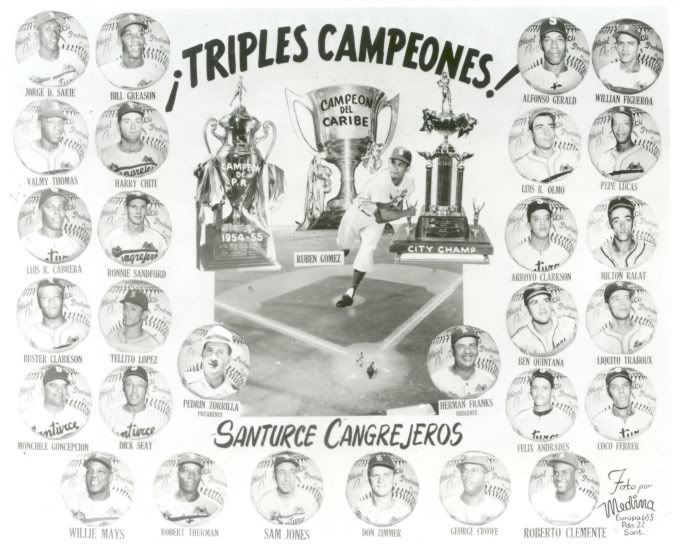

So again, you’re sitting in this stadium watching two of the most exciting ballplayers to ever grace the diamond in any stadium and they are playing on not only the same field but on the same team! Now you may ask, how does this happen. The economic reality of the game in those years was much different than today. Where today’s player makes at least six figures at a minimum, players in the 1950’s didn’t make much money. So when the opportunity to play baseball year round in an ideal setting like the Caribbean came along the ballplayers took it. In addition to making more money, players who were either Black or Latino found that the exclusionary racial environment they faced on a daily basis in the United States was virtually non existent in the Caribbean. They were able to dine and go where they wanted and were treated with respect. So, once again, you’re sitting in the stadium and have the luxury of knowing what kind of players Mays and Clemente would become. It’s easy for us to know how the players would develop, but in reality so did the Puerto Rican fans. Mays was already known and Clemente had been playing for the Santurce team from the age of 19 and he was known from his High School days as being an amazing player. So, though the Santurce team won their league and advanced to the Caribbean Series, Mays and Clemente were not the only ones who contributed. The vaunted lineup was also made up of sluggers Buster Clarkson, Bob Thurman, and George Crowe. Together with Mays and Clemente, they were known as El Escuadrón del Pánico (The Panic Squad). Also on the team was Puerto Rican legend Luis Rodriguez Olmo and a young shortstop named Don Zimmer.

Playing against the Legendary Almendares of Cuba, Carta Vieja of Panama and the home team Magallanes of Venezuela, The Puerto Rican team was able to win the round robin tournament by going undefeated (5-0). Mays ended the tournament with 2 homers and 9 RBI’s. Clemente also had one homer. Surprisingly, the MVP of the tournament was the unlikely hero, Don Zimmer, who hit 3 homers to take the honors.

There are many players that I personally could say that I wish I had the privilege to see in person. Though I could see footage of Mays and Clemente nothing could compare with seeing these Hall of Fame ballplayers in person. I can see in my head images of Mays making amazing catches with the ease that only he could. I also imaging Clemente running full speed to make an amazing basket catch then firing the ball to any base (And most times successfully) throwing runners out on the fly. I hope that as baseball fans you can imagine what I can and then some. Enjoy.